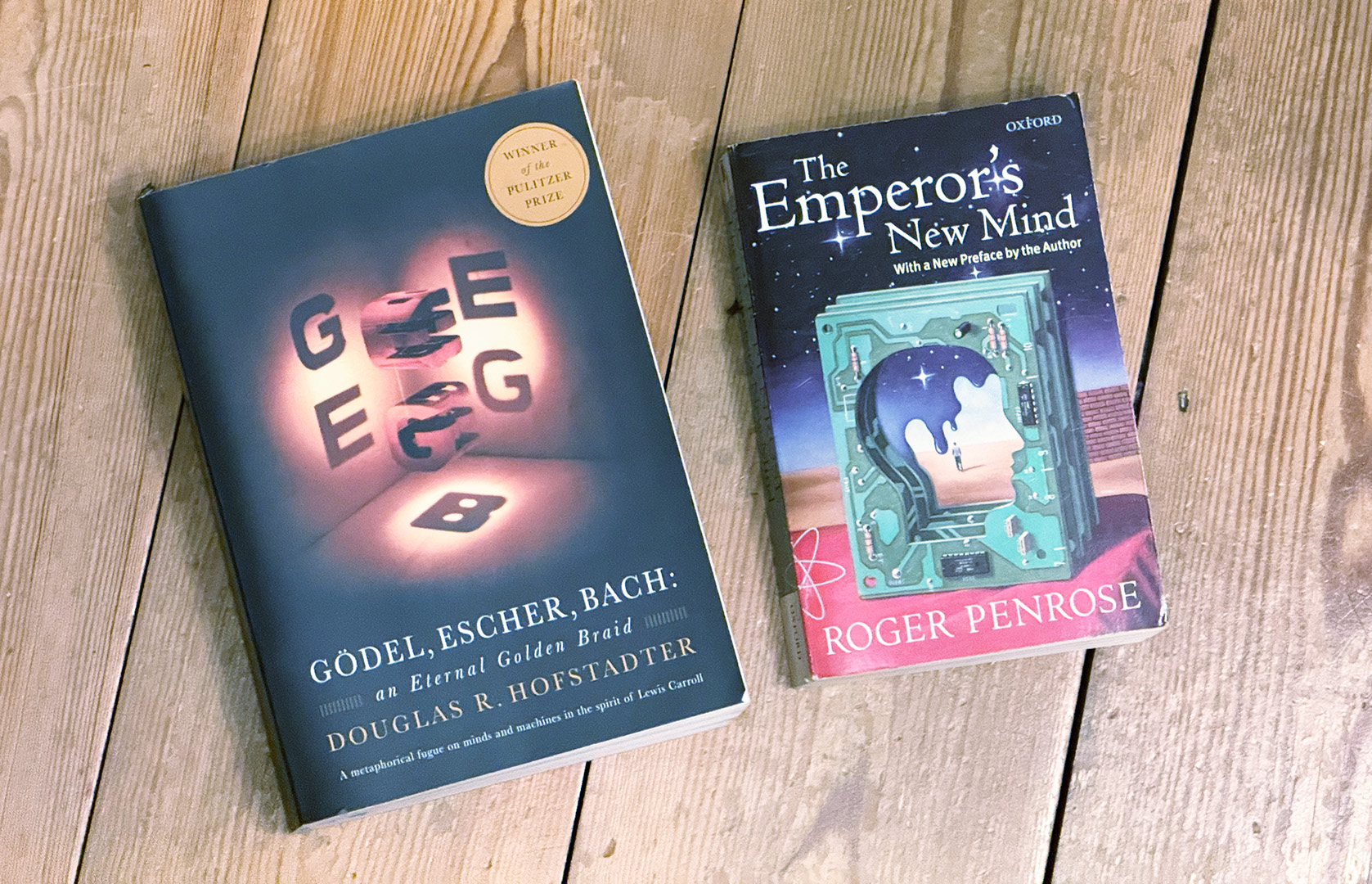

Wrestling with the theory of Artificial Intelligence is not a new thing. Two books have occupied space in my head for many years now that still have some of the best questions, at least –

The Emperor’s New Mind

Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid

What they have in common is that they attempt to deal with consciousness, and they take Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem as a basis for it.

Incompleteness as a foundation

What Gödel proved, very simplified, was that no consistent system can prove everything true about itself, nor can it even prove its own consistency. Try as you might to impose rigorous logic, there will things that logic cannot capture.

The ingenious thing about the proof of this is that it works by the very human process of recognising a pattern, stepping outside the pattern and classifying it, in a sort of meta-pattern. That leaves us with the odd situation that we are able to see that certain things are true, but unable to create rules by which we can prove them unless we allow ourselves to add new rules as they’re needed for each case.

This, of course, is all about algorithms, which aren’t just dry theory any more but something we deal with all day every day, and talk about in semi-mystical terms.

And, in a nutshell, we have formal mathematical proof that no algorithm, no matter how complex and sophisticated, can do everything.

Humans, though, are different

What both books note, though, is that we don’t seem to be limited in the same way. When we hit an algorithmic limit, we have the ability to leap outside it somehow and see things anyway.

The fascinating part is that they come to completely opposite conclusions about what that means.

For Roger Penrose, the author of The Emperor’s New Mind, there is clear evidence that the human brain is doing something non-algorithmic. Since we have proof that systems can’t do what we find ourselves doing, there must be something special about the brain’s workings that means in some way it is fundamentally different to computing. The book proposes a quantum mechanism, but that speculation is secondary, unproven, and most scientists think it’s unlikely at best. Still, the question remains, if humans can prove that computers can’t prove things that we can, what are we doing when we do that?

For Douglas Hofstadter, the author of Gödel, Escher, Bach, the fact that we can do these things implies that we have some sort of recursive ability to focus our thinking systems on our thinking systems, like an algorithm that can apply to itself. We may not know how that’s done, but if we can find out then there’s no reason why machines couldn’t do the same. And then we would truly have conscious thinking machines.

… so …?

OK, in fairness, neither neuroscientists nor the (much higher-paid) tech geniuses working on AI are basing anything they’re doing on either of these books, brilliant as they are. While Penrose, at least, is universally acknowledged as a scientific genius himself, it’s not in this field, and experts in it look askance at his efforts. Hofstadter’s book, meanwhile, seems to be as much literature as anything these days, like Freud’s.

It isn’t clear, logically, why Gödel’s work would have anything to do with thinking, consciousness and intelligence, anyway, no matter how much sense the connection makes intuitively.

But – most honest experts in both fields acknowledge that there is a gap, and although we have no knowing whether the gap in each field is the same, they are a similar shape, and that shape also has a lot in common with what both these books say. What is the difference between calculation, which we can systematise and do artificially, and thinking, which eludes explanation even as we actually do it?

I have no answers, and no expertise. I’m just a reader of things.

But I find this way of shaping the question, whether either book is on the right track or neither of them, provides a useful anchor as we wade through a never-ending tide of AI advancement. Every day it seems as though there are new capabilities and new refinements, as the systems we create become cleverer and cleverer.

Are they thinking yet?

Both books would say no, and point to what would need to change to be able to say yes, and I think that in that, at least, they’re a pretty good guide.